Black mountain country: a photo story about a journey to Montenegro

A photo story about self-discovery while travelling as a couple in Montenegro

1 — In 2014, when I landed in Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro, then went to Bar where this photo was taken, I had this feeling of familiarity that you have when travelling back for the first time to a country you don’t speak the language of, but have visited before. I had never been to Montenegro before, but during the previous summer, we made with Christine, who I met at new year’s eve 2013, our first and longest travel to this day: three weeks in former Yugoslavia, from Split to Zagreb, via Sarajevo and Dubrovnik, and right there in Bar, in late august 2014, it felt like I was back to the same country, even though I was not.

Bar seems to have been an important harbour during communism, and it’s now a sea resort, mostly for locals. Europeans or russian tourists were almost absent there, contrary to what we had seen in other towns of the adriatic coast we did visit the previous year.

2 — The first night, the first time we ventured out of our rented room, we crossed paths with goats, next to the beach, close to the harbour.

3 — The day after, the second time we ventured out of our room, it started raining suddenly.

4 — We found shelter from the sudden rain in what used to be the palace of King Nicholas the First, now a museum. We looked at the collections going from fragments of antiquity to photographic testimonies of the complexities of wars: Balkan wars, first world war and the eternal struggle against the ottomans.

I couldn’t help but think about the men and women who lived here. I imagined this place echoed of the games of the children in the garden, maybe running up to the top of the great stairs to find a shelter from a summer rain in the elegant austerity of this luminous building. Ghosts do exist obviously, otherwise why travel?

5 — “Stari” means “old” as in “Old Town”, as we learned the year before in Mostar. We took one of the buses that go to Stari Bar, a few kilometers away from Bar, on a rocky promontory, to visit this ancient fortress peculiarly destroyed by an earthquake and not by a war.

The Highway Code there must be considered by locals as something like an administrative aggression, a Byzantine regulation or Ottoman atavism, therefore, they drive like crazy in the narrow steep roads, with a disregard for life that I have seldom encountered in the west. In a twenty minutes journey, we witnessed two collisions, that the people there seem to take with a certain fatalism, in the midst of white fumes and black smoke escaping from exploded engines and broken metal.

Up there, in the old city, the ruins of middle ages buildings near patched up concrete buildings and wastelands. Yet no trace of gift shop and ATM. While we were in a narrow street between two buildings still standing, a little higher in the old town, we heard music. Vocal, magnificent music, with a very specific echo that made it so I could not identify its source. It was too warmly soulful and too perfect to come from a record. I was incapable of identifying what it was.

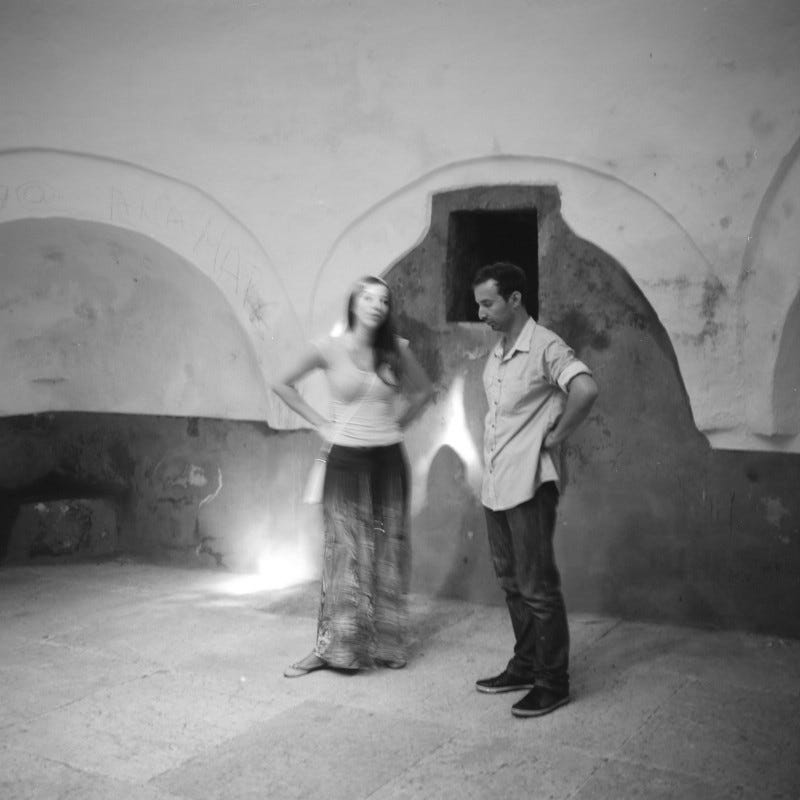

The music came from an abandoned house, actually a former Turkish Bath, empty but full of sound. The song was coming from another room, the one that was used to heat the water, the two people who were there told us. A young man and a young woman, who were rehearsing their sacred vocal music under ideal acoustic conditions. I asked in English if I could stay a little and listen and take a picture, they said yes warmly. I was profoundly touched by this music of the soul, somewhere in a cultural space between East and West, more greek than latin. I did not stay long, just enough to take a photo I knew was going to be somewhat blurred because I could not focus properly. I was unexpectedly shaken.

We said goodbye and headed higher. I was hot, I drank a lot of water from the plastic bottle I had with me. I was wondering if I could one day listen to this music again, but I left without asking what it was. I was considering coming back to see the couple and ask for information on what they were singing, but I gave up when I began thinking that in reality this mystery, this impossibility for me to name this music that shook me, was a gift I had been given.

6 — We climbed to the plateau on top of the hill upon which the old town has been built, and that towers the region between the mountains on the land side and the harbour.

We were higher than I figured.

It seemed to me we were very close to the clouds.

7 — Looking over the old rusty railing , which was almost directly above the creek below, I could see all the details of the small house that was at the bottom of the valley. The open entrance door, the large round pebbles in the half-dry water stream, the small concrete and metal bridge .

We were not as high as I thought we were.

8 — In fact we were exactly halfway between the earth and the clouds, like a tree or a cross, ready to be struck by lightning from the heavens.

9 — It was time to go back to the city. We saw it over the round roof of the room of the Turkish bath where we met the singers. I saw that the light of the room was coming through glass spheres in the roof. The singers where not there anymore, as if they just disappeared. I was trying to memorize the music the best I could while I still remembered it clearly.

10 — Back in the new town, near the Adriatic, we eat pizzas in the old-fashioned shopping center, a curiosity fashioned after the futuristic socialist style in vogue at the time of Yugoslav communism.

A very large Orthodox church was being built with modern materials but in a perfectly classic style. I walked around it, Christine stayed in front of the huge stairs leading to the entrance. A moment, while I was looking through the construction fence, a black car slowed down to my level, then the driver drove away as soon as he saw my Mamiya hanging from my neck.

The area contained the church building, but also modern homes and a religious center. There were children playing with no apparent surveillance in vacant lots.A woman was walking beyond the fences covered with half torn posters from recent elections. Behind her, children, homes, then the church and then modern housings and then the black mountains, whose summits disappear into the heavy clouds of looming summer rain.

I took a photograph.

Then it started to rain again, but the golden glittering roofs were still reflecting the summer sun.

11 — The thick blackness of the mountains from this land gave the country its name, Montenegro in the language of the Venetians, Crna Gora in the tongue of the Slavs. These mountains flow almost directly into the sea like torrent of stone, under such a low ceiling of clouds that it often covers the peaks, like the day we arrived.

In 1851 the Prince- Bishop Petar II, poet and philosopher, chose to give the money he wanted to coin the Slavic name of the god of thunder, Perun, who used to come out of the clouds in his chariot drawn by black horses and white horses, surrounded by lightning and furious eagles. The death by tuberculosis of Petar put an end to this project of currency, whose face was to have an Ouroboros. Today Montenegrin people use the euro.

I gave a few coins for the drinks we had at the straw hut on the beach. It was night and my gaze was getting lost in the darkness of the seascape.

12 — The next day we took the bus to Kotor. We briefly stopped in Budva, a city mainly devoted to the resort of thousands of Russian people staying in huge concrete residences. We left pretty fast for Kotor, a splendid, small, fortified town in the heart of the amazing geographical sea mouths, folds of land so sinuous that you can not see the sea from the port, which is at the end of the most advanced inland bay. The city itself is surrounded by several kilometers of fortified walls and fortifications, sitting directly above them. We stayed at an old lady who lives next to the Bus Station.

13 — Kotor lays in the narrow space between the the steep cliff and the bay from where you can not see the sea. It is surrounded by more than four kilometers of fortified walls that leads to a power station, emanating mists when the sun goes down, on the other side of a small bridge haunted at night by the cats of Kotor who live near the fish restaurant.

14 — Up there, a long, winding , steep road leads to the fortifications . The traces of recent or old wars mingle. The walls are crumbling and plants thrive.

15 — We went back in the city and the night fell. The churches stayed open. The fervor of the orthodox practitioners is intact, churches are crowded, they smell of incense and often resound with music. Before Saint Nicholas of Kotor I recognized exactly the melodic modulation of the female voice and that sort of male drone, it was exactly the music the young woman and the young man in the Turkish bath in Stari Bar were rehearsing.

The man who sells icons, books and souvenirs inside the curch did not speak any of the languages I know, so he said the name of the artist in his iPhone who translated it into latin letter, then showed me her name.

“Divna”. She’s a serb who has become a star of the genre with her astoundingly pure voice.

Christós anésti ek nekron,

Thanato Thanaton patísas,

ke tís in tís mnímasi,

zoín charisámenos

The incense, the iconostasis like a separation between this world and the other, the music, the people who were kissing the icons or were lighting candles, it was impossible not to feel the mystical fervor. I was uplifted by the beauty of it all.

16 — Frescoes and icons. The language of images, which reinforces or contradicts the language of the words. Images lurking in the shadows, covered with soot or in the bright light, glorious and golden. Patiently waiting for the coming of someone new to tell a truth eternal.

17 — We spent two nights in Kotor. We travelled, as we did the previous year, booking the first stay when in France, then deciding where to go depending on what we feel like once there. For the next step we decided to go to Montenegro’s capital Podgorica. Brand new capital from the Socialist era, when it was baptized Titograd in 1946, it succeeded to Cetinje, called now “capital of the throne”. They have this retrofuturistic concrete buildings that seem to have been made for an ideal society that never materialized.

18 — There is also a new European air of modernity in Podgorica. This modernity which has the architectural peculiarity of having none. Suddenly, you pass the corner of a street, everything is shining new and you could be somewhere else.

19 — But wherever you go, there is always hope for a little darkness. The hope of being able to find a dark place to let a little atavic soul exist, a little bit of ancestral intuitions, far from the prying eyes of the light bearers of progress.

20 — The monasteries, perched in difficult to access mountains, are important pilgrimage and tourism locations for the Orthodox in the Balkans. We decided to go to Ostrog Monastery, of utmost importance for Serbian Orthodoxy. It is situated a hundred kilometers from where our hotel was, in the middle of the apartment blocks and vacant lots, the only one frequented by tourists in Podgorica. Everyone travels by bus or by taxi if they don’t have a car in the area, but after a waitress told us that there was a train station at Ostrog, we decided to try train. A train of surprising modernity, with wi-fi and AC on board. It brought us calmly through the Montenegrin countryside.

21 — Once at the station Ostrog, we quickly realized that the rest of the visit was not going to go as planned. A stop, closed, lost in the mountains, overlooking a valley from which low noises reached us muffled despite the absence of obstacles, denoting the distance and the vastness of it. I tried to ask the two old gents who came down with us, “Manastir Ostrog?”. Hilarious, one of them pointed his finger to the sky behind me. Looking in the direction he indicated, I actually saw the tiny Balkan Shangri-La he showed me, on top of an impressive cliff itself located behind rock barriers. He went waving us warmly and laughing with his friend. The monastery was no less than a day’s walk away. We had to wait for the arrival of a hypothetical taxi or the next train. We had a bottle of water and two sandwiches, it was Sunday, and it was hot.

22 — The train schedules indicated the time of the next train, which was going in the wrong direction. We decided to take it anyway, we had to wait an hour.

We ate the two sandwiches in the shade of the concrete station. When you do that and you have to wait for something, you find yourself in a present that lasts. The hearing is sharpened. The wasps are busy around their nest in the beige wall near the trash. Dogs bark in the valley. The bushes on the other side of the rails bustle of the noise of invisible small animals, but no one passes, no car on the road and no walker, nobody. And the train we expect finally does not pass either. We were so desperate we decided to take any train stopping here, to go anywhere.

Then all of a sudden, an eighties navy blue Volkswagen Passat came, with an improbable sign “taxi” on it. An old man came out and started rolling a cigarette, looking at us from the corner of the eye. He did not speak a word of French or English, so we had to jabber and talk with our hands. He offered to take us to the monastery and then drive us back to the station. Christine suggested that he drove us back directly to Podgorica. He asked us for a fair price and he looked mischevious but amiable, so we agreed and went up in the Passat, while he removed the “taxi” sign from the top of the Volkswagen.

I was planning to strap my belt but he made me understand it was not worth it. Two minutes of Balkan-style driving after, I did put the belt while clinging to the armrest of the door and it made him laugh. In the midst of cigarette smoke, the eye of the old guy nonchalantly stayed on this road he obviously knew by heart. The Passat without dampers was humming in the steep twisting road, rushing between the branches of the bushes above the barely tarred road, making dust clouds, avoiding potholes the old man seemed to have a clear mental map of, since he avoided them all, maneuvering the steering wheel with his fingertips while relighting his cigarette. I got my camera out just in case.

Seeing my camera, the old guy made me understand that he knew a good place to take a photo of the monastery. At a bend, he stopped on the side of the road, I went out of the car to take a picture. I did not think, I framed in the center. The monastery was there, its purity shining in the September sun, weightless in the rock wall.

23 — Then we went to the monastery. A parking area has been made for the buses of the numerous pilgrim tourists. The old driver of the more or less legal taxi found a friend and told us to take our time. The monastery consists of a lower part and an upper part. We tried to behave in the most respectful way possible, because we are not orthodox and didn’t have any idea what we were supposed to do and not do.

In the lower part there is a chapel cave, only illuminated by votive candles. You do not see people strolling casually to take pictures there, faith in the air is thick, like the centuries of soot on the walls.

24 — To go to the upper side of the monastery, in which picture taking is forbidden to tourists like me, you have to climb a long flight of stairs where pilgrims wait in line for their turn to enter the sacred place. Priests guard the entrance of the place, which is so small one has to wait wait for someone to come out before going in. Those who come out, come out backwards, bowing their heads to fit through the hole without turning their back to holiness inside.

In the anteroom, frescoes of incredible beauty forbidden to cameras. Then the cave-tomb of the founder of the monastery, covered with frescoes whose freshness stillshines. There, a motionless priest with piercing eyes sits, half-curled on his side. He holds in his hand at the end of his extended arm a big simple wooden cross, next to the face of the relic of St. Basil, which is in the open casket. You go there and kiss the cross before heading backwards.

Basil is an Orthodox priest born in Herzegovina in the 17th century. The legend says he mastered very young the first Christian mysteries, praying, with the caves of his region as refuge. He led a life of flight and fight against the iconoclastic persecution that the Ottoman Caliphate was leading at that time against the Orthodox people. He stayed at Mount Athos then founded the monastery of Ostrog.

The role of images in the Orthodox religion is fundamental. The icons are distinguished from idols, the worship of which is strictly forbidden in the Abrahamic religions, in the sense that the icons are images that are not venerated for themselves but for the holy people they represent. In this subtle difference are held countless historic casus belli.

In the tradition of the West, images and statues are not only allowed but essential to the understanding, the transmission and the exaltation of faith.

I decided to accompany these photos with texts, while I had not written anything for a long time, after this visit. I did not take any photos of the upper part of the monastery and I was delighted. Some things are just meant to be seen, not recorded.

25 — The old man took us back to Podgorica about fifty kilometres away, still smoking rolled cigarettes in his BMW. He left us at the bus station, we said goodbye, and we walked to the city center. I did not take pictures of the frescoes of Ostrog but I took pictures of the frescoes in the oldest church in Podgorica, St. George, at the foot of the mountain which gives its name to the city, “the city at the foot of the mountain”.

The figures seem to look at anyone adventuring his eyes to look up, like adults looking at babies in a cradle. An archetypal heavenly family. The time may well erase the alpha and omega signs, but the one who must die to live again stands in the center, looking down at us, Christ Pantocrator.

26 — Behind the church lies the most dismally abandoned cemetery that I ever visited. The tombs , some of them looking very old, are attacked from all sides by plants. Some tombs were opened and vandalized at an unknown time, and recent remains of drunken night parties lie here and there.

27 — Resinous sap perfumes the place, which also exudes smells of earth and ferns. Among the trees one can see more trees on the hill, in the heat of the sun, but here in the cemetery, the stones radiate a damp cold that seems eternal.

28 — The night was beginning to fall while I was in the cemetery, and I really wanted to drink a glass of local beer.

When we left, we crossed paths with the young parish priest who was walking from the twilight to the church through the park. I took a photograph.

29 — On the last day, we ate water chestnut on Skadar lake.

30 — Skadar Lake is shared between Montenegro, to the north, and Albania, to the south. We stayed in the most northern part of the lake, near the village of Virpazar. Once we finished our boat ride, we walked to the old fortress in reconstruction that dominates the landscape. On the way to the village, I realized that we were going to go back to France very soon. I had almost finished the roll in my Mamiya. 6x6, 12 frames per roll of 120 film. As we descended the road leading to the fortress, I had a regret of not taking a picture that seemed obvious, moments earlier, of a mountain in the distance. I went back and took the photograph.

The bus that was to take us back to Podgorica never came. A heavy downpour hit us, and we took a providential taxi to return to our hotel in the former Titograd.

31 — The next day we flew to Paris where we stayed a few days before leaving the diffuse and gray light of Paris for the reassuring darkness of the South.

As soon as we were back, our heads full of images, we were thinking of going away again.

How much time do we spend in our rooms looking at pictures from the outside world, the flickering shadows of a light we never directly look at, locked in our dark rooms?

32 — What do you dream of, you, who have not yet seen our faces, what do your eyes see, that I have forgotten to have seen too?

What do you hear when you hear my voice?

I imagine that, in your obscure chamber to which you are rooted like a tree, your name, when I say it, resonates like thunder.

Antonin was born in april 2015 and his sister Jeanne in august 2016.