Into Uncanny Valley - Part 2

A look back at the exhibition, an interview with Radio FMR, perspectives on AI, projects

Foreword

Dear Seasons subscribers, old and new, what a paradox for a project which aimed to follow the slow passage of the seasons, to have skipped two in the first year! Indeed, two seasons have passed in silence since I last published the first part of this text, Into Uncanny Valley - Part 1, at the end of April, and now I'm back to share with you the second part of Into Uncanny Valley. This break in publication, far from being an oversight, was necessary because of the intense activity that I have had since and reflects a major turning point in my career, initiated by the success of the project to which these articles are attached. .

This exhibition, In the Valley of the Strange, not only marked a turning point in my practice, but also opened up new and interesting perspectives. In the space of six months, the fallout from this experience led me to integrate artificial intelligence into art, which I realized was the missing piece of the puzzle I wanted to assemble with some of my projects. I also have a growing number of image education interventions scheduled for 2024. Generative AI, in both imagery and text creation, is now an essential component of my work.

The in-depth interview carried out by Monique Blanquet, with Dominique Burdin on technique for Radio FMR Toulouse, was a highlight of this adventure during the resumption of the exhibition in November in conjunction with the work of Alice Freytet, and I thanks them. Their ability to ask relevant questions not only informed the work carried out during the exhibition, but also allows me to convey the essence of my presentations and guided visits to a wider and more distant audience. It's this experience that I'm delighted to share with you in this newsletter, offering a window onto the interactions and discussions that animated Into Uncanny Valley.

Beyond the encounter between technology and the natural world, it also reveals the complex and constantly evolving relationship I have with photography, a medium that is both familiar and constantly renewed by new perspectives and technologies.

Below you'll find a text transcript, as well as all the images I exhibited as part of my project, and other relevant images.

Interview

Conducted by Monique Blanquet & Dominique Burdin for Radio FMR.

Monique Blanquet: For Radio FMR, we're in Cahors on the CHAI site where there's an exhibition, a retrospective gesture of the 2023 edition of the Cahors Juin Jardins Festival, and we're here with Alain Astruc. Alain, hello.

Alain Astruc: Hello.

Monique Blanquet: Next to the work you presented on this 2023 edition, I believe in the hotel opposite.

Alain Astruc: Yes, it was during the whole month of June at the Best Western hotel in Cahors.

Monique Blanquet: And it's a photographic work, since that's your artistic specialty, but not the only one. But in this photographic work, you've investigated something that's of great interest to many people today, something that's the subject of debate and discussion, the famous Artificial Intelligence. And you called upon it with this echo and resonance of the garden.

Alain Astruc: What happened was that Cahors Juin Jardins commissioned me. In the DNA of Cahors Juin Jardins, it's often said that there are private and public gardens, where visitors come every year. Some of these gardens have been open to the public for a very long time, others more recently. I was commissioned to create something around the image of these gardens. So I visited 14 of these gardens and took photos in each of them, talking to the owners of the gardens, trying to understand the personality of both the owners and the gardens, what they wanted to put in them, what they wanted to project in them.

Monique Blanquet: The vibrancy of the garden, in fact?

Alain Astruc: Absolutely. And why? Because I wanted to remain faithful, not to the literal, visual reality of this garden, but to this intention, to this atmosphere, by using an Artificial Intelligence generator. So, is it a photo? That's precisely the question. What I decided to do was to show three levels of reading. So there are three sizes of print, corresponding to the three levels of reading, the three levels of involvement of Artificial Intelligence. So, first level of reading, these are small formats measuring 20 by 20cm. And they're virtually unretouched photos of gardens. Each time, it's a detail, an element that struck me as striking, that seemed symbolic, that seemed to best represent the garden in question. From this image, I generated a similar image, with similarities, but which I took with the prompts of artificial intelligence. So I generated an image that looks like the basic image, but is different.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, there's an inclusion of characters, objects, atmosphere and light. Does the AI do that? So you have to choose anyway, so that it offers several options. There are several options? How does it work?

Alain Astruc: That's what's so fascinating. So there are three levels of reading. In fact, what I wanted to say is that there are photos, there are images that are hybrids and there are those that are only made with words. So what is the nature of this Artificial Intelligence?

Monique Blanquet: With words, it's the words that trigger these images.

Alain Astruc: That's right. Until now, when we wanted to create visual works with words, what we knew was cinema, of course. You have to write a script, and that's an extremely cumbersome process. It's very long, very heavy. It's the most expensive art form, the hardest to make, the most complex to implement. So here we have an art form, a method of creation that is extremely light, but which responds to words. So what's astonishing is that it's a visual medium, but one that responds to language and words.

Monique Blanquet: And what word did this image evoke, for example?

Alain Astruc: To generate an image, we use what is called a prompt. In other words, the prompt is a natural language request. And I don't really remember this one.

Monique Blanquet: Right.

Alain Astruc: Why? Because there's a writing process.

Monique Blanquet: That's what interests me. It's the writing process that's linked to this approach and that generates an image. In the end, it doesn't matter what the word is. It's a word that creates an image, which is part of an image of a garden. And there's a kind of tree, not genealogical, but I don't know, something, a ramification, that makes art. At what point does the creative part come into play in the whole process?

Alain Astruc: So this question, as I often say, is one we've already asked ourselves at a very precise moment, when photography first appeared. I have a book I always refer to, called Je hais les photographes (I hate photographers), published in 2006, which compiles a series of excellent articles by French intellectuals of the 19th century, including some great intellectuals I'm very fond of, like Baudelaire and Lamartine. They say that photography is the art of charlatans, that the photographer doesn't do anything, he just presses a button. Who is the author of the image? The camera, not the photographer, of course.

Monique Blanquet: Okay, it's a never-ending debate that's already been raised.

Alain Astruc: It's a debate that's already been raised and settled.

Monique Blanquet: And then, with AI, it's the same thing.

Alain Astruc: So we say, it's a machine, well yes, but a camera is a machine. What we didn't know in Baudelaire's day was that technology can be tamed in an intimate way. It can be controlled by intuition, by feeling, by means, even through body language. In photography, there's a habitus with the camera, a complex relationship with the subject, which we know can create something specific. For example, when you put two photographers side by side and ask them to photograph the same thing with the same camera, it's never the same.

Monique Blanquet: Well, yes, it's the dimension that actually makes the difference, that makes the identity and the artistic proposition. So we saw this first panel. Well, I didn't describe it, but it's branches with maybe a cherry blossom.

Here we are, and finally it ends with what looks like a Swedish or Norwegian fantasy series.

Monique Blanquet: Right, right, right. And does it have titles or not? Yes ? No, the general title is "In the Valley of the Strange".

Alain Astruc: If there's a very specific reason for Into Uncanny Valley, it's that in the 70s, a Japanese roboticist (Masahiro Mori) theorized what's known as "uncanny valley". This is the idea that the visual imitation of a human being is all the more disturbing because it looks like a human being, but not enough, because it makes us think of corpses. So, for example, a representation that doesn't resemble a human being at all, such as a crudely drawn robot, can be quite nice, but a total imitation doesn't disturb us because we can't see the difference. And when it's not quite the same, there's that moment when the valley corresponds to a graphic like that, there's a moment when it's very, very disturbing.

Monique Blanquet: Strange.

Alain Astruc: And it's been a frontier for a very long time, this frontier, I think we can now say that it was crossed in February during the preparation of my exhibition, since I had already decided to call it Into Uncanny Valley, but there was an update in the stakes engine, which meant that all of a sudden photorealism took us to the other side.

Monique Blanquet: Ah yes, fascinating. So, the other panels, is it the same principle? Are they different?

Alain Astruc: I can talk about that.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, I see cats. There are cats. There's a young woman who could be a painting from another time, but what happened there?

Alain Astruc: The cat is quite simple. It's in the garden that houses Marc Petit's sculptures. I didn't want to rework these sculptures, but this cat lives in the garden. And I said to myself that what I was going to do was transform this cat into a bronze statue. So it's a version of this cat in another universe that's suddenly transformed into bronze.

Monique Blanquet: And the figure of the young woman?

Alain Astruc: Well, that's interesting, because when we generate these images, we generate four at a time, we choose one, we don't choose any, we start again. And the way we choose them is very similar to the way we edit photos. In reality, we know very well that all photographers, and I was talking about this yesterday with my colleagues, we know very well that we take 200 photos, sometimes one is good, sometimes it's the first one that's good, sometimes we take 300 and we have trouble. And there's a habit of knowing which one is the right one, really. And this one, I remember generating a lot of images, and this one wasn't like the others.

Monique Blanquet: It's made its mark, it's out there, it's true that it's very strong.

Alain Astruc: It's ambiguous.

Monique Blanquet: She's a strong presence. That's it, exactly. Alain Astruc: Quite astonishing, for me, which I didn't find in the others. So that's it, there's this creative process that's all about iteration, in other words, instead of being about the labor of constructing an image, it's more about iteration and choice. And how you turn it into a work of art, well, that's choice, guidance and integration into a more general project.

Monique Blanquet: Of course. Alain Astruc: I'm going to talk about two images, this one in Valérie's garden. She wasn't necessarily the happiest, she was surprised because I found an object that she'd wanted to throw away for a long time and that I found. It's two little children, a rather kitsch statue of two little children with a hole in one of the statues. And the resulting image is a tree trunk with a child trapped inside in a totally impossible, surreal way.

Monique Blanquet: There's a hole in it all the same, we find the hole.

Alain Astruc: There's the link. So we find the elements, the hole is there, the two children are there, but one of the two children is in the hole. Who's in the tree. And he's alive.

Monique Blanquet: He's alive, and there's the plant. All this is interwoven, and to finish, there's an echo, a sort of circle around a flame on the edge of a lake. Here too, we're in a microcosm, in a strange cosmos.

Alain Astruc: Absolutely. That's true, because what I also wanted to do was to circumscribe this series of images, so that in my imagination, they all take place less than 25 km from here.

Monique Blanquet: It's all about the territory.

Alain Astruc: It's all linked to the area. It's all rooted here, at least in the imagination. And this is the history of the Lot and Quercy, revisited. And it's an alternative history. So this is the story of women beside a river who celebrate fire. And it seems that one of them is making a fire with her hands.

Monique Blanquet: A bit of a witch, perhaps. Perhaps.

Alain Astruc: It's possible. I don't know what they do, but I like it.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, it's a form. There's a form of narrative that operates from your sensitive material. In that sense, there's obviously a creative dimension. But now we're in front of another panel. A mossy vegetation, an undergrowth with a small stream. Trees that look a little ominous.

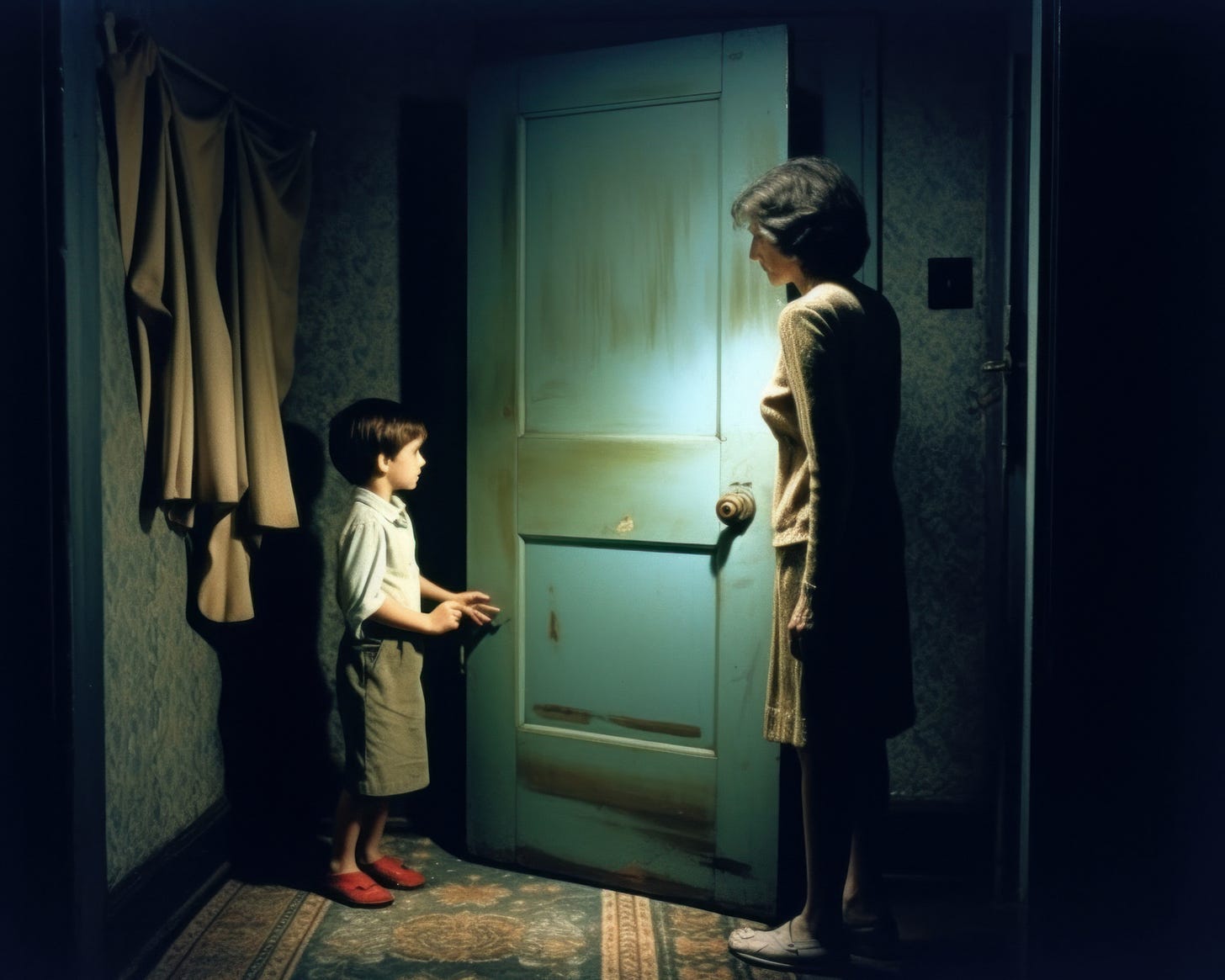

And then, opposite, there's a boxwood labyrinth library in a plush house. And a very British boy watching us.

Alain Astruc: That's it. We were talking about anchoring. Now there are two anchors. That's interesting. It'll allow me to bounce off something else. The photo of the mossy landscape appealed to people here because it reminded them of something. And indeed, for me, it's the Célé valley. I deliberately described something that is the Célé valley. And it comes out in this way... You don't know if it's too realistic or not. It's almost that, but there's something strange about it.

Monique Blanquet: There's a real atmosphere that emerges. And we all have an echo of the landscape. It's also a landscape that settles in. And afterwards, it's empty of humans. And the link with the labyrinth, the library and the child?

Alain Astruc: Well, in the course of the work on generating the images for the exhibition, it has to be said that it's a very laborious job, not in the sense we know from painting or photography. The labor is elsewhere, because it's quite complicated.

Monique Blanquet: In terms of research, how does it work?

Alain Astruc: What's difficult is the iteration, the number of generations you have to go through to refine the words. And what I've discovered by doing a lot of it, is that the use of language brings out the unconscious, the passive. So I was in the process of selling my family home at the time.

Monique Blanquet: Childhood, the family home.

Alain Astruc: It just came out.

Monique Blanquet: The boxwood labyrinth.

Alain Astruc: People who know me saw right away what was happening. And so it's a good example, in my opinion, of transformed biographical inspiration, since there's nothing that's true. It's not me, it's not real. There's nothing literal about it. But this subconscious inspiration, it's surfacing on the surface and it's coming out through the machine.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, you mentioned the three levels of reality. And there's an artificial dimension, but one that's rooted, the one you're talking about, the magic of words. And at the same time, it's true that there's this taste for a form of classical photography.

Alain Astruc: Oh yes, yes. Because in my photographic work, I don't do that at all. It's more of a French tradition, it seems. In other words, intimate, humanist, unretouched photography, closer to the diary and the diarist than to staged photography. And I think that's also why I didn't feel threatened by these images, because for me, it's something else. It's not photography, it's adjacent to photography. It's a world that's not far away, it's a relative, a cousin, and it uses some of the elements of photography. But photography requires you to be here, present, in a place, at a time, in relationship with people, with place. And that's an exploration of the imaginary.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, there is an imaginary world, but it's nourished by this new factor, Artificial Intelligence, which has already invaded our lives to a considerable extent, and there's more to come. Of course, there are fears and doubts, but there are also enthusiasms, because like all phenomena, it's only logical that artists should seize on this material and turn it into a creative vision.

Alain Astruc: I also think that, in fact, what has fascinated many visual artists about this technology, as soon as it appeared, as soon as it was sufficient to create something, is precisely this exploration and rediscovering this role of explorer.

Monique Blanquet: Of looking, in fact.

Alain Astruc: And the absence of moral judgment, in other words, the artist doesn't ask himself whether it's good or bad, he goes right to the end of his process, he presents, he asks questions, he helps to ask questions and he doesn't really answer.

Monique Blanquet: Well, that's another matter...

Alain Astruc: That's interesting too, because we were talking about biographical elements. This is a moment I remember very well from my adolescence that I recreated. It takes place at Mont Saint-Cyr in Cahors. And it's nighttime, I'm a teenager, with three friends.

Monique Blanquet: You're high above the city, watching the city lights.

Alain Astruc: And that's an evening I remember very well. So none of it's true, because it's all false.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, the question of what's true and what's false is a persistent one in these proposals. But ultimately, yes, that's not what's at stake. True and false, it's the result that's there and that's proposed. So there's this vision of adolescence, but it's also linked to the plant forms proposed here.

Alain Astruc: So here's a photo of the Pont Valentré, seen from the Best Western Hotel, with its characteristic chairs, and I've transformed them into an alternative Pont Valentré that's been split into two. And there's an effect, I find a little charming and comical, of this juxtaposition of what's real and what's not. You wonder what it's all about...

Monique Blanquet: You can't tell the difference a priori. Maybe that's what's so nice about it. And then this shape...

Alain Astruc: So it was taken here, it's in the cellar here.

Monique Blanquet: In the CHAI garden, which is also the subject and heritage of the Juin jardins association. There's a permanent garden here. These wooded structures are permanent. So there's always a link with the garden. And here, we haven't seen everything. You want to know more about each panel.

Alain Astruc: So, what's going on here? We were talking about prompts. Earlier, people were saying to me, "What's a prompt? What did you ask? I could find it because it's archived. Often, the reality is that I don't really remember. Because work is evolutionary. You start with one, you modify it. And it's in the modification that you end up finding it. Precisely which one, I don't know. But one thing I do remember is that I was talking about Borges. Jorge Luis Borges. And in fact, the structures at the center are books. And it's a labyrinth of books. So there's the idea of Borges' labyrinth, of the garden.

Monique Blanquet: That's great.

Alain Astruc: I don't remember exactly what it was. And it's pretty typical of the kind of back-and-forth you can have with the machine. Because that's what's a bit disturbing. And what's fascinating is that it responds in a way that we haven't always anticipated. And sometimes it's not what you want to hear, but sometimes it's a good idea. So it's serendipity, we use it, we take it somewhere else. There's that dialogue.

Monique Blanquet: And next to this photo, there's a sort of neo-romantic work based around ruins, a horse, a sky, a Rembrandt-like penumbra. And then there's an echo. Because if you put them together, does that mean there's a link between the two or not?

Alain Astruc: Yes, for me anyway, there's a geographical link, because for me, everything happens 25 km from here. Right, then. So maybe there are different time strata. But for me, it's all happening in the same universe. Maybe it's even, maybe this, this garden, maybe it's the garden of the house in which this one takes place. So, we see a woman dressed in typical nineteenth-century fashion, in a white dress, in semi-darkness, looking through a wall that's absent in her house. And through this wall, we see a superb horse neighing beside a ruin, also typical of the 19th century, while its interior is filled with water.

Monique Blanquet: There's a kind of... Yes, it's completely dreamlike. It's...

Alain Astruc: So, this is a juxtaposition of two doors.

Monique Blanquet: There are doors.

Alain Astruc: That's right. So, one of them is a garden shed. And the variation, so it's the garden shed that's in the garden of the lady in question, and the variation, which is quite astonishing, is that the dining room side...

Monique Blanquet: It's the same.

Alain Astruc: Yes, but it's on the wall, and what's inside and what's outside is a little disturbed. There's someone inside, there's a woman. Maybe you'll see that there are many female apparitions in the gardens.

Monique Blanquet: But completely phantasmagorical. And the importance of light is very painterly. These pieces are very painterly.

Alain Astruc: There's a door that leads to a dark interior that you can't see. There's another inside, leading to a luminous outside.

Monique Blanquet: It's open, by the way. It's a pictorial dimension, a form of abstraction, almost.

Alain Astruc: There are flowers visible here, projected onto the walls.

Monique Blanquet: A sort of reflection, an echo. It's like... And this is something else again.

Alain Astruc: So, this one walks with the one next to it. Maybe we can describe them. They're two vertical images of women with fire, in the same series.

Monique Blanquet: Like the one we saw earlier.

Alain Astruc: It's from the mythical past of a Quercy region that I'm not sure ever existed.

Monique Blanquet: Dressed in animal skins and plant hats. That's it. So, a kind of hat, too, with this flaming stump.

Alain Astruc: A burning bundle.

Monique Blanquet: A burning bundle.

Alain Astruc: Is it a witch, a shaman, I don't know. Underneath, then, that's funny. When I say that images are created from words, there's also the possibility of wordplay. So here we have an insect hotel in the garden. It's a small structure that allows insects to nest and take shelter. And I turn them into an insect hotel. It's a Haussmann-style insect hotel.

Monique Blanquet: Double game, double word. That's it.

Alain Astruc: This is the forest project at Cabessut. It's the forest garden.

Monique Blanquet: Forest garden.

Alain Astruc: So the forest garden as it is now. And the forest garden as it will certainly be in 30 years' time.

Monique Blanquet: Ah yes, an interesting projection. A projection of the future. Interesting about the future. It allows you to do that too. So there you have it. We find the echo, the creature. It's a creature that's been created. There was a show where I think there were characters like that.

Alain Astruc: So, I did...

Monique Blanquet: Some time ago, during the Cahors Juin Jardins festival, there was a character you played who was in this very atmosphere.

Alain Astruc: Yes, yes. I did an exhibition called L'Homme Sauvage et le Bal du Sauvage. So it's true that I'm interested. It's a folk costume tradition, extremely inventive. And this is...

Monique Blanquet: Pagan.

Alain Astruc: Yes, that's right. It's probably part of a pagan tradition. It's a woman again. A stag's head. A woman with a stag's head.

Monique Blanquet: Plants in her hair and on fire. And still fire.

Alain Astruc: Fire, water, women.

Monique Blanquet: Yes. The elements that... And here, a garden in which we see...

Alain Astruc: A garden hose.

Monique Blanquet: A garden hose that has been transformed into a stream in the artificial intelligence version, shimmering with a woman in the garden.

Monique Blanquet: And people who...

Alain Astruc: And this is the garden shed, Emmanuelle's garden, where she holds... writing workshops for women. And so, in the imagined version, there's a woman writing in the garden.

Monique Blanquet: Who writes in the garden, that's it. All this has a kind of coherence in... Not in incoherence, but in irrationality. There's a form of coherence in the irrational. In formidable. Very good. How was this exhibition received? What feedback have you had?

Alain Astruc: Well, that's just it. I threw myself into it. I was very happy to have this project, to be trusted with it.

Monique Blanquet: And it was at a time when we were really starting to talk about the general public aspect of Artificial Intelligence. Incomprehension.

Alain Astruc: Frank hostility.

Monique Blanquet: Ah, outright hostility.

Alain Astruc: Outright hostility. Frank, really aggressive on social networks and so on. So I thought, what am I going to do? It doesn't matter, I'll do it anyway. And then, when it was done, I was very surprised, it was a real success, I think. A lot of mediations, a lot of people coming to ask questions, a lot of people discovering a reality they'd never imagined.

Monique Blanquet: Yes, it makes sense.

Alain Astruc: To put it bluntly, I'm neither for nor against this technology. I think it's an important advance, and like all technological advances, there will be uses that will be bad for us. Yes, of course there will. And some that will be good. There you go. I use it to make art. I agree. I see it as another tool in the palette. There's photography, video, writing, music. And now there are AI images as well.

Conclusion

This interview with Monique Blanquet closes for me this chapter devoted to the exhibitions of Into Uncanny Valley, and I hope to have conveyed to you the essence of the guided tours that I had the opportunity to give to an often curious public and hungry for answers. Many thanks to Monique, Dominique Burdin, and Radio FMR for this interview and permission to reproduce it, and to Christine for proofreading.

I fully intend to continue my publications here, although without a fixed frequency. Seasons will remain my main publishing platform on the Internet, the change being that I will undoubtedly open it to developments in my artistic career, including in the field of AI and films, but I still have a lot of posts from photography pending.

My upcoming projects include:

• Leclerc and Hargreaves: The Arctic's Silent Requiem: A 1983 mockumentary about a lost Arctic expedition from the 1920s, produced entirely via AI.

• Experimental film project: Exploring the ambiguity between still image and video, fiction and documentary, writing and music, live action and AI.

• AI Image Education Workshops: Combining the history of AI, presentation of my work, and practical workshop.

• Workshop at the MGI in Paris in January 2024: In collaboration with the Albert Kahn Museum and the B.A.L.

• Upcoming publication of a printed monograph on Into Uncanny Valley in French published by Cahors Juin Jardins, available for sale at the beginning of next year.

Limited edition chromogenic prints of 7 copies of all the images from the exhibition that you can see in this article are also available for sale.

Thank you to the owners of the gardens, to Isabelle Marrou, Alice Freytet, Emma Cluzet, Emmanuelle Sans, to the Best Western Divona Hotel and to the CHAI.

I sincerely thank you, the readers, for your patience and loyalty. Future publications will certainly be more frequent and probably shorter.

Thank you with all my heart, and see you soon!

Alain

Links

My social networks : X, Instagram, Facebook.

My site : alainastruc.com.

Radio FMR : radio-fmr.net.

Cahors Juin Jardins : Cahors Juin Jardins.

Into Uncanny Valley - Part 1

Great read, Alain. Thanks.