On a Book by Serge Tisseron and a Persistent Misconception About AI

Memory, image, generative intelligence: what I took from Serge Tisseron’s latest book, followed by a clarification on a common misunderstanding about artificial intelligence.

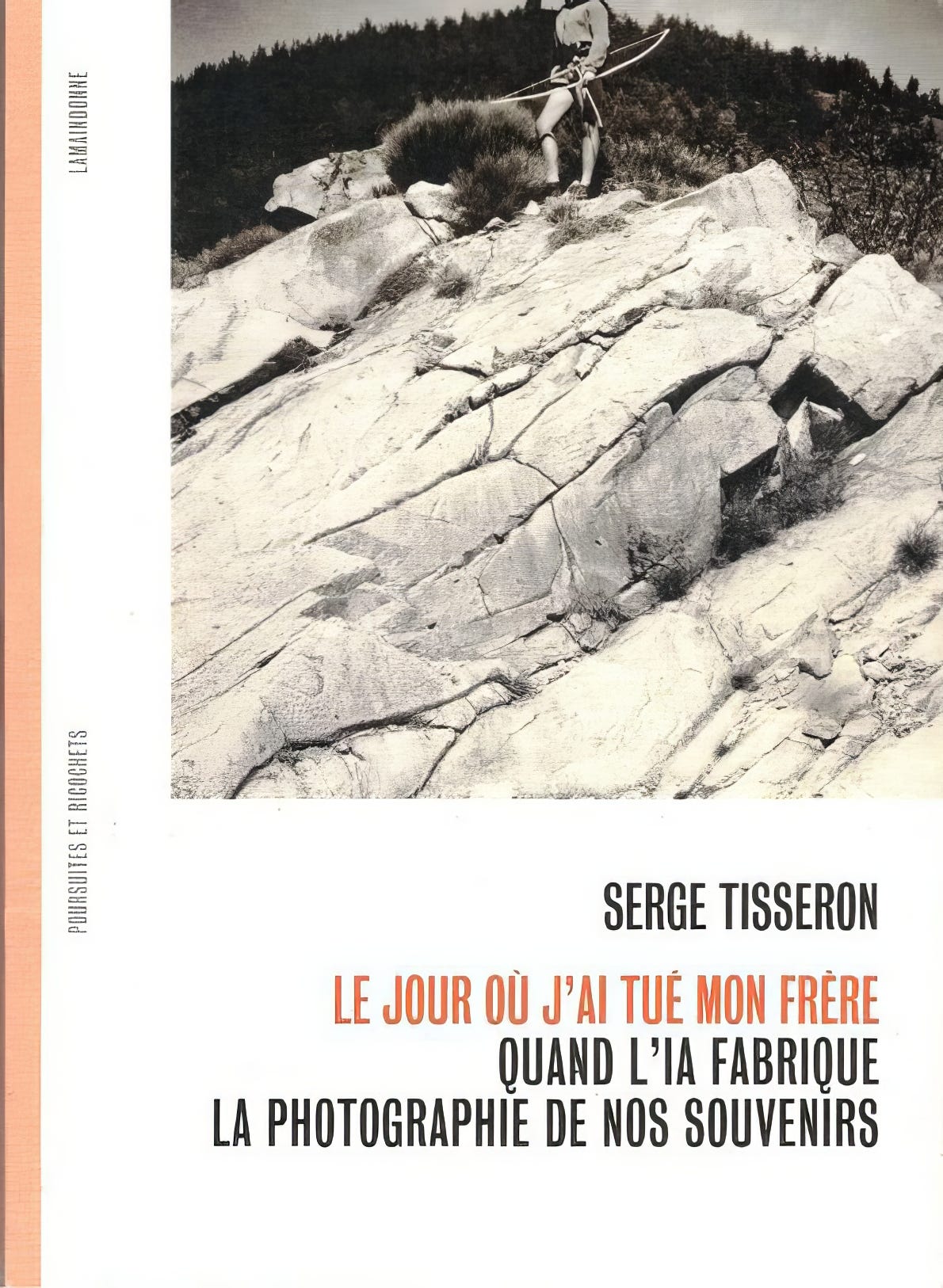

Part 1 - Serge Tisseron’s Book “The Day I Killed My Brother – When AI Manufactures the Photographs of Our Memories”

1. Who is Serge Tisseron

Serge Tisseron is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and doctor of psychology. A member of both the French Academy of Technologies and the National Digital Council, he has devoted most of his work to exploring our relationship with images, family secrets and emerging technologies. In the 1980s, he gained recognition for identifying, through a close reading of Tintin albums alone, a hidden family secret in Hergé’s life, an intuition later confirmed by the author’s biographers. He was among the first in France to examine the transgenerational effects of trauma and secrecy, and to analyze the psychological impact of television, video games, and later, robots and digital environments. He has published over forty books, including Shame, Family Secrets: A User’s Manual, Psychoanalysis of the Image and The Day My Robot Loves Me. He has also contributed significantly to photographic theory and curated major exhibitions. Today, he focuses on artificial intelligence and its effects on memory.

2. Summary of the Book

In The Day I Killed My Brother, Serge Tisseron begins with a childhood memory: a play scene with his brother in the 1960s, which he is convinced was once captured in a photograph. He remembers a mock duel, a symbolic victory, and a picture taken by their father. But when he looks through the family album, the photo is missing. He then tries to reconstruct it, first by drawing it, then by generating it using various AI tools.

This attempt becomes the starting point for a broader reflection on memory, the power of images, and the ways in which AI changes our relationship to the past. The experience he describes is both fascinating and unsettling. The generated image does not exactly match the memory, yet it starts to impose itself. It risks replacing the uncertain, living blur of memory with a fixed image that is partially inaccurate but visually convincing.

Recognizing this discomfort, Tisseron develops a firm critique of AI. In his view, it only copies. It searches databases, applies models, but lacks creativity and subjectivity. It functions as a system of reproduction without genuine transformative capacity.

The book weaves together personal narrative, psychoanalytic theory, and quantum metaphors including Schrödinger’s cat to explore the contradictions of memory. It closes with a vision that is both poetic and cautious: a world in which people could recreate the missing images of their lives, not to falsify reality but to transmit it more clearly, while remaining vigilant about the risks such tools might carry.

3. What I Agree With (And Where I Differ)

The strongest point in Serge Tisseron's book, to my mind, is his intuition about memory. He reminds us that human memory is uncertain, partial, and constantly being reconstructed, and that AI-generated images mirror that very process. On this point, I agree completely. It’s not just a theoretical idea for me. It’s something I’ve seen with my own eyes in workshops. I’ve watched people look at an image generated from a memory and say “it’s enough”. Not because it’s accurate in every detail, but because it captures the essence. Because it feels right.

Where I diverge from his analysis is in the fear that AI could "rewrite" our memories. That concern seems misplaced. An AI-generated image simply reflects what it’s been given. If the memory is blurry or imprecise, the image will be too. The AI doesn’t betray anything, it only makes visible the uncertainty that was already there. The real question is not whether an image is faithful, but whether we are ready to accept that perfect fidelity was never the point.

In my view, this fear comes from a generational bias. For those who grew up believing that photography faithfully documented reality, the appearance of a “fake” photo can be disorienting. But younger generations never saw photography as a guarantee of truth. They already live in a world of malleable, filtered, remixed images. To think that AI-generated pictures will somehow overwrite the family album is to assign photography an authority it no longer holds.

And honestly, if Serge Tisseron had asked a painter to illustrate a memory, he probably wouldn’t have felt the same discomfort. What troubles him here isn’t the image itself, but the fact that it mimics the visual codes of photography. Yet this link between photography and reality has always been a fragile construction, and image manipulation didn’t begin with artificial intelligence. What has changed is the scale and intimacy of the act of creation, which is now within reach of anyone.

Part 2 – The machine that steals and pastes

1. A widespread misunderstanding about image creation

During the many workshops I have led in schools, high schools, and with artists, I’ve developed the habit of asking participants a simple question: “In your opinion, how does an AI image generator work?” Almost every time, the answer is the same. That’s when I realized just how deep the misunderstanding runs.

Once, at the end of the first hour of a two-hour session in a high school, a young woman raised her hand and said, “This might be a stupid question... but does the machine actually create images?” I paused for a moment and replied, “Yes, of course it does. That’s literally what I came here to show you.” I realized then that this wasn’t obvious to her at all. Despite my entire presentation, the very idea that one could create an image from nothing hadn’t clicked. I was struck by how difficult it was to grasp what now seems so simple.

Another time, during a session where a small group of teenagers had access to MidJourney, I noticed something similar. The girls quickly started typing prompts and playing with the interface. But it became clear they thought it was a search engine. I told them, “This is not a search engine, it creates images.” To my surprise, they didn’t believe me. They thought I was joking. To them, it was obvious these images were just being pulled from somewhere else, that they already existed. And honestly, given the speed at which MidJourney now generates results, it’s a completely understandable mistake. I had never considered that before. So I proposed an experiment: I asked them to suggest something impossible to find online, and I showed them the image being created live, right before their eyes.

Over time, and after reading countless online debates with people who simply refuse to budge from their position, I’ve come to understand how people imagine these systems work. And I’ll break it down in the next section.

2. The most common mental model

Here’s what I’ve come to understand as the mental image most people have when they think about how an AI image generator works:

The AI goes online and grabs images. It steals them, copies them without asking for permission, and stores them in massive databases on its servers.

When the user types a prompt, the software behaves like a search engine. It looks for images that best match the request, and then assembles a clever collage from the material it has on file.

It’s a simple vision, intuitive even, almost logical. But it is entirely false. And as long as we remain stuck in this framework, we cannot understand what these tools truly change in our relationship to images.

3. What AI really does - the simple version

A generative AI does not steal images and does not make collages. It operates in two stages that are quite different from what people usually imagine.

Training It was given millions of images, each paired with words or captions. It analyzed them to find very subtle correlations between visual forms and language. It did not keep these images. It extracted statistical patterns from them. A kind of blurry but powerful understanding. It learned. It did not steal.

Generation When asked to create an image, it does not fetch anything from a database. It starts from random noise, like static on a TV screen, and gradually transforms it into an image. This process is not a search. It is a creation. The final image did not exist anywhere before.

4. What AI really does - the technical version

Image-generating AIs like MidJourney, DALL·E or Stable Diffusion do not store images. They do not copy any. Their process relies on two main phases, both rooted in deep learning: training and inference, meaning generation.

Training The AI is first trained using supervised learning on hundreds of millions of images, each paired with captions or keywords. These images are analyzed by a deep neural network, often of the transformer type. The AI does not store the images. It extracts statistical correlations from them and encodes these as mathematical weights. What it learns is a set of visual patterns associated with language, not memories of pictures.

Generation When a prompt is entered, the AI does not retrieve anything. It generates an image from scratch. It starts from random noise, a cloud of meaningless pixels, and uses a diffusion model to transform it step by step into a coherent image. This process takes place in what is called latent space, an abstract mathematical representation. At each step, the AI denoises the signal using what it has learned, until it produces a fully computed, never-before-seen image.

In short, the AI does not copy, search or paste. It reconstructs using probabilities, creating something entirely new.

5. Why these clarifications matter

Why insist on technical details? Why take the time to correct a common misconception? Because it is not a minor issue. A large part of the ethical anxiety surrounding artificial intelligence today stems from this very confusion.

Let us be clear. Image generators do not steal. They do not assemble fragments of existing photos. They do not replicate artworks found online. In the United States, where most of these models were developed, their training relies on the principle of fair use, which allows transformative use for the purpose of analysis and learning. It is not theft, it is a statistical operation.

This does not mean that everything is automatically ethical. But if we want to ask the right questions about memory, creativity or truth, we must begin with facts. As long as we remain trapped in the idea of an algorithmic photocopier, the conversation stays shallow.

So what about copyright? Why does the impression of transgression persist? Because there is real ambiguity, not in the way these models work, but in the legal and symbolic frameworks around them. Copyright law was designed for a material world and physical distribution. It was already shaken by the rise of the Internet. It is now being challenged again by AI.

What is true, and should be acknowledged, is that the creators of these models used millions of publicly available images without asking for permission. They did so within a legal framework that allows it, based on a broad interpretation of fair use. And they did so because it would simply have been impossible otherwise. If they had needed permission for each image, these tools would not exist today.

This raises moral questions, certainly. But we need to distinguish between thoughtful criticism grounded in fact and emotional reactions fed by misunderstanding. The ethical debate can only improve in quality if it starts from a clear understanding of what is really happening.

Conclusion

I recommend reading Serge Tisseron’s book. In the French intellectual landscape, it is rare to see someone engage directly with AI, to test it, narrate it, and reflect on it. His thoughts on memory are nuanced, sensitive, and often accurate, even if I do not share all of his concerns. And it is precisely that concern, so widely shared, that I wanted to address here.

I am not an AI researcher, but I work with these tools, I test them, and I try to speak about them honestly. If I have simplified too much or said something incorrect, I welcome corrections. What matters is asking the right questions.

This text is also a call for education. The gap between what these tools can already do and what the French National Education is prepared to address is becoming more serious every day. Ignoring or banning is no longer enough. We need to learn, to teach, to explore. Invite outside voices. Create spaces for discussion. It is better done imperfectly than not done at all.

Finally, the workshops I mentioned are drawing to a close. I have taken notes throughout the process. Soon I will share a separate piece about what I observed and learned, about memory, image, and what AI can still help us uncover between the two.